“The being was, indubitably, a woman. In the soft garment which it wore stood a body, like the body of a young birch tree, swaying on feet set fast together. But, although it was a woman, it was not human. The body seemed as though made of crystal, through which the bones shone silver. Cold streamed from the glazen skin which did not contain a drop of blood […] But the being had no face. The beautiful curve of the neck bore a lump of carelessly shaped mass. The skull was bald, nose, lips, temples merely traced. Eyes, as though painted on closed lids, stared unseeingly, with an expression of calm madness, at the man—who did not breathe.”

(Thea von Harbou, Metropolis, 1927 [1925]: p. 46)

Metropolis (1927) is one of my favourite films of all time. It’s also one of the most important films of all time, which can only prove that my taste in film is unimpeachable. Made at the height of the German Expressionism movement by the husband-and-wife powerhouse of Fritz Lang (who directed it) and Thea von Harbou (who wrote the screenplay, which was adapted from a serialised novel she wrote beforehand), it illustrates a glittering dystopia: society fractured by gross inequality, where the businessmen and suits live in the literal upper-echelons of the grand city, while the workers that sustain is toil away in the subterranean power stations. Dissent and revolution are on the lips of all the disenchanted lower-class workers, pacified only by the sermons of the incandescent Maria (Brigitte Helm). Equally captivated by Maria is Freder Frederson (Gustav Fröhlich), the leader of Metropolis’ son who is eager to learn about the side of his society that he has been blissfully ignorant of his whole life. He attempts to reconcile the two sides of Metropolis’ coin before blood on the streets begins to flow, coming into opposition with his father Joh Frederson (Alfred Abel) and the mad scientist Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), who has created a maschinenmensch – literally ‘machine-man’ – that takes Maria’s form to sow discord amongst the masses and bring Metropolis to its knees. Ultimately, Freder – the man born of Metropolis’ riches who walks among its common folk – becomes a peace-broker between Metropolis’ two factions, embodying the film’s core message that ‘the mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart.’

The early history of cinema is laced with nitrate tragedy. It is estimated that 90% of films made between 1890 and 1940 are lost, either due to their thoughtless destruction at the hands of studio executives wanting to free up space in their inventory (the same tragedy befell 97 episodes of Doctor Who from the 1960s by the BBC), poor archival maintenance, or because the nitrate contained within film-stock in the period, when improperly stored, would spontaneously combust. There is more than one story of one reel of nitrate combusting and destroying an entire archive of early cinema. To this day, Metropolis is one of those tragedies. The 153-minute epic was mercilessly cut and re-edited to 90 minutes when it arrived in America, and its poor reception in Germany at the time meant that the excised hour was lost.

Attempts were made over the decades to reconstruct Metropolis. Most famously, music producer Giorgio Moroder scoured archives over the world throughout the 1980s for missing footage and photographs to create his own cut, which included the controversial choices of colour-tinting the black-and-white image, using rotoscoping techniques for dynamic colouring and replacing the inter-titles with subtitles. None was more controversial, though, then creating an entirely contemporary score for the film, hiring such artists as Bonnie Tyler, Pat Benatar, Freddie Mercury and Adam Ant to write and record songs to play throughout. The soundtrack was notable for being the very first to be recorded completely digitally, with its release being prioritised for CD at a time when vinyl was still king. The response to Moroder’s cut was venomous condemnation for ‘dumbing down’ the film for the MTV Generation. Mercury’s single ‘Love Kills’ was nominated for a Golden Raspberry (‘Razzie’) award, the dark shadow of the Oscars ‘celebrating’ the worst of cinema.

Moroder’s auteurist reinterpretation of Metropolis led a renewed charge to reconstruct it as Lang had originally envisioned it. The efforts of film preservationists around the world eventually yielded a 120-minute cut in the late 90s and, in 2008, a damaged dupe 16mm print of the whole film in an Argentinian archive. In 2012, after extensive restoration work was undertaken on the recovered print, ‘the complete Metropolis’ was unveiled to the world for the first time since 1927. Alas, two scenes were damaged beyond repair – approximately two minutes – but inter-titles were used to ensure their narrative beats were preserved in the film. One of cinema’s greatest tragedies found a happy(ish) ending nearly a century later. What a story!

The prevailing cultural memory of Metropolis is undoubtedly the Maschinenmensch, whose slick futuristic art deco design became the benchmark by which all robots in cinema and adjacent visual media would be compared to. Designed by Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, Brigitte Helm played the Maschinenmensch not just while it is impersonating Maria, but also as the robot itself. Alas, though, the beautiful sculpted costume was destroyed during production. When the false Maria is burned at the stake and took on its robotic form again, it was really burning down. That breathtaking, uncanny creation, gone up in smoke, ironically paralleling the struggle to reclaim Metropolis over the next few decades.

I could spill so much ink on why Metropolis is a masterpiece of cinema, social futurism and the direct ancestor of so many techniques, themes and aesthetics seen in the art industry today. But this is Stereodyssey, so let’s keep the discussion to 3D. As the original Maschinenmensch was destroyed, attempts have been made over the years to recreate Maria, but without any in-depth information on how it was made beyond the grainy silent footage and a few production stills, most of those attempts have a hefty amount of artistic license to them. That all changed in 2014 when the propmaking company Kropserkel collaborated with WSM, who hold the rights to Metropolis, and the Schulze-Mittendorff family to faithfully recreate the Maschinenmensch, based on Schulze-Mittendorff’s design documents and other reference material. The result, as you can see in this unveiling video, is an unimpeachable replica with a thoroughly spine-chilling presence.

Kropserkel’s Maria has travelled the world for various exhibits. In 2017, the Science Museum held a Robots exhibition, featuring both historical automatons, conceptions of robots and popular depictions in media. How could I resist going along to it? Maybe one day I’ll make a blog post of the different robots on display there, but the centrepiece of the whole thing was the Maschinenmensch, flanked by a semi-circle of mirrors refracting the robotic image and ever-shifting lights casting the sculpture in different colours. To see it with my own eyes, while studying film and beginning to appreciate everything that this sculpture represented, was as humbling as it can get.

I went to the Science Museum with my university’s Sci-Fi and Fantasy Society, who went to different exhibits, so I couldn’t stay long there. But even then, I spent most of my time in front of this display. I wanted to capture it in 3D, but the shifting lights and other people around would’ve made sequential photography too difficult, so I settled on my Fujifilm W3 3D camera, which got the job done, despite the subpar quality and fixed depth.

… Or so I thought. I mean, they’re OK – close up, they capture some nice detailing and tones on the sculpture. But none of the stereos captured the dizzying totality of that whole display: the glowing foundation, unearthly, casting Maria in a base heavenly light; the mirrors, splitting Maria in so many different directions, catching glimpses of the other displays around it. Had I tried to get a picture of the full display with the W3, the depth would have been non-existent, making the whole thing fruitless. I had to go back.

A couple of months later, I met up with my pal Jim – a bigger Metropolis geek than I am – after I told him about the exhibition. Although I was there on a photography mission, we were so excited to see the Maschinenmensch that we never got a picture with her together, something I regret. I have a picture with her from my first trip, but seeing her with Jim – someone who got how incredible it was – was something to cherish.

Getting this shot as a sequential stereo was a tall, tall order. The light colours were changing almost constantly, resting on a shade only for a couple of seconds before shifting to another. I decided to go for the golden light on Maria, largely because she is interpreted as golden on the poster for Moroder’s cut and, even though she’s actually silver, the gold hue is iconic. Now, if you mistime the shot, you’ll get a different colour, which would blow out your eyes to look at for any amount of time in 3D and would require a lot of correction in Photoshop to get anything resembling a consistent result. In short, you have to get the first shot at the tone you want, adjust your parallax and then have get the second shot at the perfect time to get the same tone, lest you wait for the colours to cycle through again. Adding to this is the human factor: namely the fact that this was a public exhibition and people can turn up at any moment to spoil the consistency of the shot.

With so many environmental factors against you, a stereo like this is impossible without a lot of patience, razor-sharp reflexes, resilience and a potent instinct for parallax distance. All things I absolutely do not have. Definitely not back then, at least. But, another factor that plays into these situations is luck, and I don’t mind telling you that I got extremely lucky.

This is one of my favourite stereos that I’ve ever produced. The colours didn’t need any alteration at all, I stumbled into the exact timing between light cycles. It’s almost perfect, save for a slight parallax imbalance where if I moved just an inch or so more between shots, the distance between the Maschinenmensch and the bars that flank her would be perfectly even. Oh well. What good is perfection if us mortals can actually grasp and preserve it in our work? The contrast of the purple background and the yellow light – complementary colours, of course – looks so nice here. Plus how the light bounces across the mirrors. Maria is reflected four times in the mirrors behind her, in-between fractions of the exhibition around her. Some contrasting and other adjustments later, and we arrived at the finished product.

For me, it perfectly captures the uncanny mystique of the Maschinenmensch: the lighting is so chiaroscuro, with the eyes shining, peering through the shadows splashed across her face. For most of my stereos, I use a grain filter to give it a more analogue feel (and to cover up any pixelation/artefacting by saying it’s an artistic choice) and the shadows really complement it here. I never get tired of it.

This is where the story would end, but there’s a little more… I have no idea where Kropserkel’s Maria is nowadays – probably in an another exhibition in another country – but she’s far from the only Maschinenmensch out there. As I said before, she has beguiled countless others to try to recreate her in the absence of the original, but they’ve always strayed from the original design in some way. My friend Jim has seen one in a museum in Berlin, which I hope to see one day too. But for now, let me take you from 2017 to 2022. A film student no more, I now had two degrees and was in Paris for a week to speak at an academic conference. I’m staying about a 20 minute walk from the Cinémathèque Française, the place in France for cinephiles. So the story goes, the likes of Jean-Luc Goddard and François Truffaut often went to screenings there, informing their concept of cinema when they pioneered the French New Wave of the 1960s.

On my off-day, I went there and saw they had a permanent exhibition called the Musée Méliès, dedicated to preserving and presenting the work of Georges Méliès, who we would call the father of what we understand now as cinema. I spent at least two hours in the exhibition, falling in love with its documentation of early cinema and being in the company of Méliès’ actual film camera and the coat he wore in Le Voyage dans la Lune (1902) – trust me, there will be a post about this exhibition and the embarrassing amount of badly-lit stereos I took in full at some point!

But what caught me off-guard was seeing Maria there, in the section about how Méliès’ pioneering work inspired other filmmakers. What’s special about this Maschinenmensch is that Schulze-Mittendorff himself was commissioned to make it in 1972 by the Cinémathèque Française! That’s insane

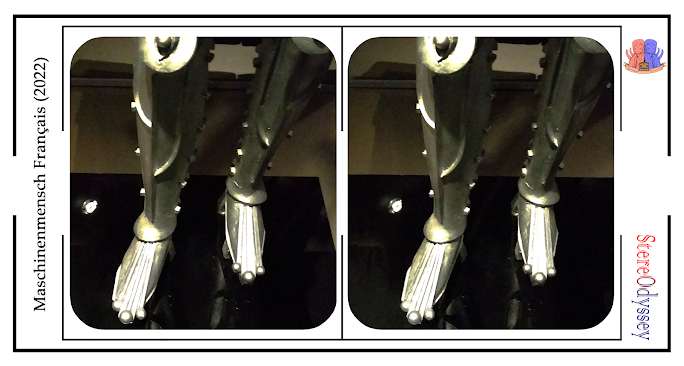

The mood-lighting was not friendly to my phone’s picture quality and the glare of the glass showing other areas of the exhibition creates an interesting double-exposure effect, but hopefully you can get the gist of how this Maria looked. Being sculpted by Schulze-Mittendorff, this is about as authentic as you can get to the original, yet there are some interesting deviations, probably because he wasn’t working to the same specifications that he was from fifty years ago. The structure is overall thinner, probably because this Maria is not made to be worn. The head-dress has points protruding outward, while the original (and the Kropserkel version) has those points stay within the perimeter between it and the head. The eyes are a bit narrower, creating something of an intense expression, completely losing the eerie vacant look of the original.

The coolest revision, though, are the feet. In the original and Kropserkel versions, they are sculpted as boots, with some embellishments to the sides. Schulze-Mittendorff’s replica, though, gives Maria three ball-like toes, with lines running through the foot like metal bones. This immediately called to mind von Harbou’s description of the Maschinenmensch in the Metropolis book of being crafted as human without the blood and tissue: crystalline skin, metal bones, traced features. It’s a weirdly more organic take on Maria, making her more uncanny as she is neither human while still not being completely machine in appearance. I dig it.

Of course, this opens up a question: which one is more authentic? The one working to Schulze-Mittendorff’s original specifications, or the inaccurate one (re)made by Schulze-Mittendorff himself? It’s a conundrum with perhaps no definitive answer, but the world needs more maschinenmenschs, so there’s no point pitting them against each other. One day soon I hope to return to the Cinémathèque Française and take much more higher-quality pictures – I was completely ambushed with what was in display in there and didn’t have the best resources at my disposal. Maybe one day their Maria will have a display as amazing as the one Kropserkel has to fully revel in her significance. For the time being, she’s in good company with artefacts of Méliès’ masterpieces.

Check out Kropserkel’s page on making the Maschinenmensch here: https://www.kropserkel.com/robot.html

Comments

Post a Comment